Table of Contents

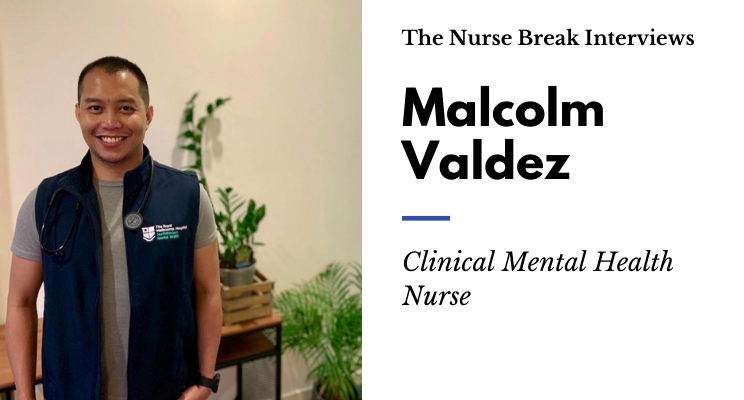

Meet Malcolm Valdez who is a Clinical Mental Health Nurse (Registered Psychiatric Nurse) who moved from the Philippines to Australia and is now currently working in the specialist units of Neuropsychiatry & Eating Disorder Units at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. Keep reading to learn about all things Psychiatric Nursing!

Tell us about you and why you chose psychiatric nursing!

I’m originally from Manila where I completed my Bachelor of Science in Nursing and received a Registered Nurse qualification.

When it came time to pick what I wanted to study after secondary school, I had lots of ideas running through my head and found it hard to settle on one. My eldest sister was studying medicine, so I thought a healthcare career could be interesting. I wanted to do medicine too, but in the Philippines, to become a doctor we have to do a bachelors degree related to healthcare, before applying for a Doctor of Medicine program. I choose the nursing program for my Bachelor’s degree because you can work in the field as soon as you graduate and experience what’s it like working in a clinical area. I had the intention of then applying for the Doctor of Medicine but I enjoyed nursing so much that I decided to continue my nursing practice.

After working as a nurse in the Philippines for almost two years, I moved to the UK where I furthered my qualifications with a Postgraduate Diploma in Leadership and Management in Health and Social Care. I also completed a Masters of Business Administration, specialising in healthcare finance.

In 2016, I moved to Melbourne and in 2019 I commenced a Masters of Advanced Nursing Practice in Mental Health at Univerity of Melbourne, of which I’m currently completing the final subject of the course.

When I’m not working, I go to the gym and run in the park, play video games like Starcraft or Red Alert (pretty old school lol), and enjoy travelling internationally – pre-Covid, of course. My favourite country to travel in is my home country, the Philippines – I’m a bit bias I know. The best trip I’ve done there was going island hopping for a week, walking on the sandbars and snorkelling. The views are amazing and it really feels like a paradise!

What different areas of nursing have you worked in?

I’ve been everywhere in my nursing career — which is fun! I worked in accident and emergency, triage nursing, consulting clinics, a birthing unit, a post-anaesthetic care unit, general medical and surgical units, aged care, neurology, orthopaedics, paediatrics, rehab, palliative care, learning disability, mental health and alcohol and other drug withdrawal units.

What makes a good mental health nurse?

This is a tough one to answer. I would say your personality and communication skills are crucial components of being a mental health nurse. Sometimes the biggest communication problem is that we often listen to reply rather than listening to understand.

Providing patient-centred care is important but is often challenging for most clinicians for varied reasons. Also, adaptability in your surroundings will help you in the long run and accepting that recovery does not consist of ‘getting better soon’. Remember that you cannot help everybody. Always ask for advice, feedback or help. Remember you’re not working alone.

Mental health nurses are troubleshooters. They will try to provide a pragmatic approach to a difficult situation and sometimes do a calculated risk assessment. Your solution-focused skills will be your friend and paramount in doing a risk assessment. Reflecting on when I worked as a general nurse, I always remembered the medical mnemonic of ABCD. In mental health, we have a similar mnemonic with a different meaning. Every time I’m providing care, I always make a risk assessment based on the mnemonic ABC: A – assume nothing, B – believe nothing, and C – check everything.

Finally, “good” mental health nurses I admire and look up to are empathic, resilient, have curious minds, and able to look further than just the presentation of the client. Don’t forget that once in a while you should find something to laugh about. It’s human nature. That makes us sane.

You studied in the Philippines. What were the first few years like?

Studying nursing in the Philippines is a bit competitive and tough. We don’t have breaks in between semesters, and we continue studying for 4 years! We have to learn all aspects and specialities of nursing from the fundamentals to leadership and management (you name it, we have it all). There are additional requirements to graduate from a bachelors degree which include completing five of each of the following: normal labour and delivery care, newborn care, assisting in a Cesarean section, minor surgery assist and major surgery assist.

We don’t have a graduate program in the Philippines, but there is a similar process. It involves taking a nursing licensure exam, also known as ‘board examination’, after graduating with a 4-year bachelor degree. If you’re lucky enough to pass it, you’ll become a registered nurse (RN) and be able to work as a junior nurse immediately.

My first year as an RN was nerve-wracking. It felt so bizarre because you’re basically on your own and no one is supervising you. As we don’t have a clinical nurse educator role, I relied heavily on my peers and senior nurses. We had training, exams, and seminars every three months, but I felt that it was not enough to boost my confidence to work alone.

I noticed a big gap between what was being taught in uni and working in the field. Textbooks were an excellent way to get information, but I found myself improvising a lot of the time. We tried to follow and apply evidence-based practice approaches, but we usually didn’t have the correct resources or equipment pieces.

I remember, at times we (nurses) had to chip-in and buy IV antibiotics for our patient because they didn’t have the money to pay for it. In that first year, I struggled a lot but learned so much!

What was the transition from the Philippines to Australia like? What is the process involved?

During my transition to practice in Australia, I had to take the English exam and needed to prove that I was a practising RN in the Philippines. I also had to complete an intensive three-month nurse training program with a written and oral examination and clinical placements.

Now the process is a bit different. You still have to prove your recency of practice, take the English exam and online nursing multiple choice question (MCQ) exam (similar to NCLEX in the US), then fly to Australia and take the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE).

What are the main types of patients you see in your current position and what is your role in their care?

I currently work in a specialist mental health unit – neuropsychiatry, eating disorder and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) – as a Registered Psychiatric Nurse.

My specific area within the unit is split into two parts – neuropsychiatry and eating disorders – so our cohort are very diverse. In neuropsychiatry, we usually have an older population who suffer from Huntington’s disease, motor neuron disease (MND), acquired brain injury or movement disorders, along with clients who need deep brain stimulations, genetic testing or a diagnosis clarification.

Most of the time it’s like playing Dr House (from the US TV show, House) because you need to thoroughly investigate a client’s history, try to get collateral from family, and assess their clinical presentations.

We also cater to genetic research and try to determine if abnormal genes can cause psychotic symptoms like Niemann-Pick type C disease (NPC). This disease is relatively new and occurs from a rare, inborn error in metabolism attributed to autosomal recessive inheritance of mutations in the NPC-1 or NPC-2 genes and affects approximately 1 of 89,000 pregnancies worldwide (Wassif et al., 2015). The disease is characterised by progressive neurodegeneration and early mortality associated with organic or psychopathologic conditions or illnesses (Klünemann, Santosh, & Sedel, 2012; Bonnot et al., 2014).

Our clients may undergo neuropsychiatric investigations such as lumbar puncture, brain scans and numerous blood samples. Further examinations may also be needed in determining their condition such as assessments of mental health status, neuro-cognitive ability, navigation assessments, swallowing test, sleep studies, electroencephalography (EEG), and body movements just to name a few.

Our eating disorder unit serves adult clients with severe eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa binge and purge subtypes, eating disorders non-other specified, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder.

We usually monitor client’s blood levels, in particular, their electrolytes to make sure that they’re not going through re-feeding syndrome, abnormal heart rhythm or worse, a cardiac arrest. We complete electrocardiograph (ECG) reports and interpretations and escalate if the client is deteriorating medically.

We also provide therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing (MI), art therapy, and support them during and after mealtimes, including meal preparation. We also strictly monitor their caloric intake and utilise nasogastric tubes for feeds, but only as a last option.

What is one thing you wish you would have known before you started your career in this field?

I wish I had known how difficult it is to transition from a general nurse to a mental health nurse.

It came as a shock to me to find that specific interventions are done differently. I had to learn the risk assessments, the mental health act, and the difference in accountability as a mental health nurse. I also didn’t realise that I would need to understand the biopsychosocial aspect of care and psychopharmacology.

I admit that it was a big learning curve, but it was a rewarding experience because I had great support from management, educators and senior clinicians.

How do you manage patients who are refusing to consent to oral intake of food?

It depends on the circumstances, but I usually start by introducing myself as a clinician and building rapport. I try to find common ground like hobbies and interests. Then I try to listen to their concerns, what happened before their admission, and their understanding of their diagnosis. Giving them autonomy by providing them with options for treatment is also an important aspect of care.

Moreover, acknowledging how they feel is essential, following psychoeducation and the impact of their actions on their physical health. I also provide sensory modulation to help them minimise their eating disorder cognitions. Good rapport can take a while to build and needs a space where the client can feel safe and supported.

When all nursing interventions have failed, depending on the risk level and medical condition of the client, I might ask for deliberation with the treating team which can include dieticians, social workers, and psychiatrists.

The outcomes of deliberation can vary but, as a last resort, we might initiate a restrictive intervention under the Mental Health Act (2014) and prescribe an assessment order until a psychiatric consultant has reviewed the client. This will allow us to provide necessary treatment such as nasogastric feeding for a client who refuses care and/or may cause harm to themselves or others.

During this time, the client will be provided with legal advice, guidance and support by linking them to legal aid and offering the chance to obtain a second opinion. I might also have to support clients in making an appeal to the Mental Health Tribunal.

How do you manage challenging behaviours?

I find it challenging when a client is floridly psychotic, has a language barrier and is unpredictable.

When a patient is escalating and becoming highly aggressive, my advice for non-RPN is to seek help immediately. Always be up to date with a client’s management plan, activate your alarm code, be mindful of your escape routes and provide the client with space until support arrives in the unit. Know the client’s psychiatric history and their triggers. Try to call a qualified translator if necessary. Allocate tasks to your team, and ensure that they know their role in these situations.

It is crucial that you are aware of the client’s PRN medications and carefully plan your interventions. Do not provide care on your own and always look for a buddy. I always tell my junior staff members “I’m not looking for a soldier here, I’m looking for a nurse”.

What would you say are the most difficult aspects of the role?

It is hard to tell if clients are experiencing psychosis or cognitive impairments. You have to carefully assess the client because if you give an unnecessary PRN medication, their symptoms might worsen. It takes a lot of time, experience and a critical eye to differentiate the two. I struggled initially, but with the support from my team, I’ve learned some tricks!

What is one myth or the common misconception that you want to debunk?

I think a lot of people believe that mental health nurses are lesser than other nurses and are lazy.

I have come to understand that there’s more to mental health nursing than just being at your patient’s bedside. For example, at least every hour, we have to assess a client’s mental status, which is known as CRAAM – Clinical Risk Assessment and Management. We also have to be somewhat like a social worker and counsellor, manage and de-escalate client’s aggression, and monitor their well-being and physical health.

I think that this myth is perpetuated by those who have not worked in mental health when they see a client transferred from a mental health unit to a medical unit. For example, when I worked as a general nurse, I remember some of my colleagues asking questions about mental health nurses such as “How come they don’t do IVs in their unit?” or “How come they can’t take care of their deteriorating patients?”.

The reason for this is that a mental health unit is set up to have a clear focus on just that – mental health. We also need to be hypervigilant of drug misuse, self-harm and/or harm to others, which occurs at a much higher rate in mental health clients. In order to do this, we reduce the amount of medical equipment in the unit and, if a patient requires advanced physical care, we will transfer them to a medical unit where they can be properly looked after.

What is some advice for nurses to better prepare themselves for mental health nursing?

Regarding education, try to find a course to gain experience with ECGs, basic life support, IV cannulation, and venepuncture. It may also be a requirement to have a postgraduate qualification in mental health to work in the field, but this varies by state/territory.

Learn to plan and prioritise your work – be an organised freak. Remember, that it’s okay to make mistakes, but it’s vital to learn from them too! Be open to experiencing other specialities in nursing. I never thought I’d be specialising in mental health. I always thought I’d stay in the emergency department and become a trauma nurse.

I am reminded of a quote from Steve Jobs:

“Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle.”

I know it can be nerve-wracking or intimidating, but my advice is not to be afraid to ask for help. Remember that nursing is a caring profession, and you are lucky that you are surrounded by caring people.

What are the most rewarding parts of your area of work?

One of the most rewarding parts is when I get to see, my clients recover from their illness and return to their everyday life where they can live without fear of stigma.

When I think about all the patients and their loved ones that I have worked with over the years, I know most of them don’t remember me, nor I them, but I do know that I gave a little piece of myself to each of them and they to me. In my mind, those threads make up a beautiful tapestry of my career in nursing.

You are passionate about the holistic approach to recovery. What is the Tidal Model?

Transitioning from a general to mental health nurse was a great learning opportunity for me to reflect on my practice and understand the importance of clients’ self-management and recovery.

From my experience in general nursing, I felt like we exploited and focused on the different treatment plans for a particular condition, but sometimes we forgot the essential aspect of why we were at our client’s bedside in the first place. We liked to believe that certain things were fixed or stationary.

When I learnt about the Tidal Model in uni, it reinforced my values as a nurse and made me understand that recovery is not a smooth sailing process. Recovery involves growth, setbacks, and periods of rapid and little change. What’s important is that, as a health practitioner, we should be in the presence of people who believe in and stand by the person in need of recovery. This can be done by understanding what is relevant and essential for the person and what kind of help they believe they need to continue with their life.

I found that I could build a stronger relationship with my clients’ by acknowledging all the richness and depth of their experience and seeing them as people and not as a diagnosis. This helped me explore their story and encouraged the individual’s greater participation in their assessment and treatment decisions.

The Tidal Model of care matched my perspective in helping my clients deal with their difficulties in their daily lives by helping them rediscover their voice.

How do you destress after a shift and selfcare?

Pre-COVID isolation, I would typically go to the gym, practice taekwondo or archery, play video games, hang out with mates and travel.

Since we’re in lockdown, I try to do mindfulness, home gym, video chat my family or friends. Sometimes we do online trivia nights or play online games with friends.

You have to be creative, especially now that it’s a bit difficult to go out.

Can you share some night shift tips?

It’s always good to plan before your shift. Try to organise the paperwork well ahead of time and prepare for the worst-case scenario. (Those code red, yellow, greys and black will eat up a lot of your time!).

Drink plenty of water and coffee and don’t forget those crisps, chocolates, and doughnuts (I’m a sweet tooth, so I always have some sweets in my bag). Oh, don’t forget to share it too!

What would you do if you weren’t a nurse?

I’m always interested in travelling around the world and had worked in three continents. So I would say a travel journalist.

What’s in your lunch box!

Coffee (loads of it), pastries, chocolates, chips, veggies and fruits. Something I can nibble is good.

Can you think of a really funny situation you’ve had while nursing?

I remember when I was in my birthing unit rotation as a student nurse in the Philippines.

I was asked to do a standard delivery procedure with my clinical educator to a primigravida woman. She was not contracting much, so my clinical educator asked me to stay in the room, along with a second patient while she checked on her other 18 patients. After a few hours, my patient began to scream in pain, and her uterus started to contract more frequently. I immediately asked my friend to call for help. Next thing I knew, I was delivering her baby.

A few seconds after delivering my patient’s baby, I heard the second patient groaning. When I opened the curtain, I saw the baby’s head and realised how quickly it was coming out. Luckily I caught it in time! Everything went very fast. I didn’t even manage to change my gloves! My clinical educator came back into the room to see me with two happy babies and two happy mothers. (Obviously, I have to make a report because I didn’t manage to change my gloves — But hey, I lived to tell the tale).

What has your experience been like as a guy who nurses?

When I was training to be a nurse, my patients would almost always address me as “Doctor”, and I immediately informed them that I was a student nurse. They looked confused, and some would ask if nursing was my stepping stone to become a doctor. Others would sometimes refuse being seen by a male nurse and preferred a female colleague, but then I charmed them with my charisma.

Now I feel that it is more accepted in society that a man can be a nurse just like a woman can be a doctor.

My advice is to wear the title of a nurse with pride. Not many people are capable of doing what you do, and even fewer are capable of doing it with the charisma and passion you do it with.

What is next for your nursing career?

I’m still open to new experiences nursing has to offer. I want my career to develop into an advanced practice level and become the agent for change that our mental health service needs, especially as the findings from The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System will soon be released.

Reference

Bonnot, O., Klünemann, H.H., Sedel, F., Tordjman, S., Cohen, D., & Walterfang, M. (2014). Diagnostic and treatment implications of psychosis secondary to treatable metabolic disorders in adults: a systematic review. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 9(1), 65.

Klünemann, H.H., Santosh, P.J., & Sedel, F. (2012). Treatable metabolic psychoses that go undetected: what Niemann-Pick type C can teach us. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 16,162–169.

Wassif, C.A., Cross, J.L., Iben, J., Sanchez-Pulido, L., Cougnoux, A., Platt, F.M…. Porter, F.D. (2015). High incidence of unrecognized visceral/neurological late-onset Niemann-Pick disease, type C1, predicted by analysis of massively parallel sequencing data sets. Genetics in Medicine, 18(1), 41–48.

Enjoy this article? Check out our other mental health related articles HERE

For more info on MH nursing go to Australian College of Mental Health Nurses Inc (ACMHN)

You must be logged in to post a comment.