Table of Contents

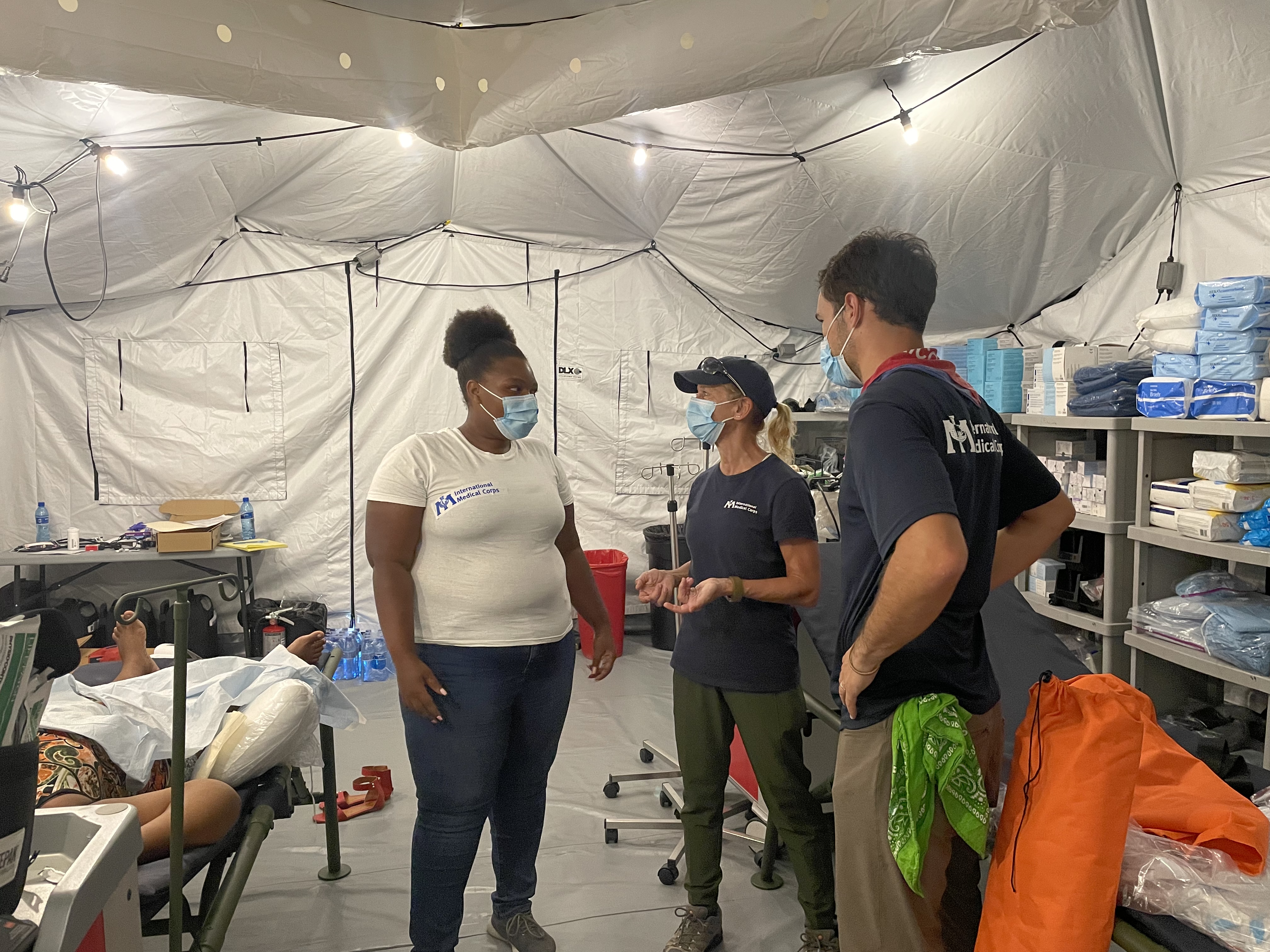

We teamed up with International Medical Corps to interview one of their senior humanitarian nurses Susan Mangicaro who talks to us about what it’s like nursing abroad in disasters. International Medical Corps relieves the suffering of those affected by conflict, disaster and disease, often in difficult and dangerous environments. You can find out more about how to get involved here.

Introduction

I graduated from Nursing School (BSN) in 1982 and finished my MPA in 1994. I’m from Syracuse, New York, and I currently reside in Naples, Florida. I have a son, Eric, and daughter-in-law Madison, who live and work in Los Angeles. We love to travel the world. I think we all have the travel gene! I am an outdoor and endurance enthusiast. I’ve completed three Ironman competitions, two ultramarathons and 13 Marathons. In November 2020, I did a 280-mile charity bike ride from Ft. Myers to Key West in 2.5 days.

For more information about how Susan got into humanitarian nursing, go to the bottom of the article.

Where have you travelled as a humanitarian nurse?

Hurricanes and Earthquakes in Haiti

In addition to my first experience in Haiti in 2010, I travelled back to Haiti one year later. I was amazed to see that it seemed as though not much had changed. Some of the rubble had been cleared, but many of the destroyed buildings looked the same. There were more tents, too many to count in some regions, most used for housing, but some clinics were still using tents. One stark difference was that the system for healthcare delivery had advanced.

Recovery

No longer in the immediate aftermath of a sudden onset disaster, the system was now in a state of recovery. Our clinic, still housed in a church, now operated as a true primary care clinic. Staffed primarily by local people and a referral network, it was serving some of the medical needs of the local community. I was once again struck by the resilience of the people. People who had suffered so greatly but yet were still hopeful and appreciative, and I was repeatedly humbled.

The long walk

I have also travelled back to Haiti several times as the organization continued its work and established mobile clinics in remote locations. Patients typically had to walk, sometimes many miles, for follow-up care. I recall one gentleman who had a significantly infected ulcer on his foot. He walked over 10 kilometres up a mountainside in Fondua, where we had a clinic once a week, to have his wound cleaned and to pick up new supplies for the following week until we returned again.

He was extremely grateful, patient and never complained about his situation. I thought how much he and so many others had gone through and continue to go through, and somehow it did not seem fair. Feeling conflicted about what so many of us have and so many others do not is a common theme in humanitarian work. I think it inspires us to continue to work in this field and work as hard as we can to provide the best care for the most vulnerable people. It inspires me on a daily basis. If I have a hard day or focus on my own problems, I refocus on what I’ve experienced, and it helps put things into perspective.

Hurricane Michael and Earthquakes

I have continued to travel to Haiti on several occasions for other disasters, like Hurricane Michael and most recently in September 2021 with International Medical Corps for the 7.2 magnitude earthquake that struck that island.

I served as the Team Lead for their Emergency Medical Team (EMT) Type 1, and that trip reminded me of why this work is so meaningful. In June 2021, the WHO classified International Medical Corps as an EMT Type 1 provider (Fixed and Mobile). Within 48 hours of an assignment, we can deploy and set up a field hospital capable of providing outpatient services to a minimum of 100 patients per day (Fixed) and 50 patients per day (Mobile). It is the only NGO in the world with these capabilities.

We had over 200+ patients on our first day of clinic in Haiti. For over two weeks, since the earthquake struck, many people had not had medical care and had crush fractures, infected wounds, and other post-earthquake medical needs that simply went unaddressed. The suffering was great. We saw as many patients as possible but had to turn away many due to our operating hours.

While we were far from the civil unrest that was occurring in Port-au-Prince, we could not keep our clinic open in the evening. Not only for security, but the staff worked long hours, in the extreme heat and humidity with very short breaks, managing crisis after crisis. The work is difficult, but every single individual there gives their all and is compassionate and caring—something that keeps you coming back.

Tropical Typhoon in the Philippines

One of the strongest tropical typhoons (wind speed 313 km) to hit the Philippines struck in 2013. I was again part of the initial assessment team on the ground. We travelled to remote parts of the islands that had been slammed with this storm system. The destruction was wide, and the needs were great. We were able to conduct the assessment, set up several remote clinics to help with initial triage and care for those who were without resources.

Ebola in Liberia

In 2014, I was a part of an initial assessment team for Heart to Heart during the Ebola crisis. I believe this was the first time I was afraid of going into a crisis. At the time, the Ebola crisis was out of control, treatment was not available, and the spread was growing in Liberia. We drafted a concept note that resulted in an award to help the agency set up an Ebola Treatment Unit.

I was asked to serve as the Team Lead. However, I was working full-time in another role and was unable to stay on for the response. This was my first exposure to a pandemic. I recall seeing a taxi try to drop off a woman who was in labour at one of the hospitals we were visiting. The facility had an outbreak of Ebola in the maternity ward and was unable to allow the patient to come into the facility. The woman’s husband was in tears. There was no place to bring her. It was the peak of the crisis and the hopelessness at that time was palpable.

Earthquake in Nepal

In 2015, a 7.8 earthquake struck Nepal causing massive destruction in the region. I was a part of the initial assessment team and continued the work as Team Lead for Heart to Heart. The quake hit not only major populated areas but also many small towns and villages in the surrounding region and foothills of the Himalayas.

We were assigned to an area in the foothills. Since we weren’t able to travel by ground transportation, our team hiked several miles to our assignment, and several local workers helped transport our supplies. As we hiked, we passed several small villages where people would come out and greet us with “Namaste” and a smile despite their situation—losing most of their belongings and their homes.

I recall hiking over rubble and crushed housing, seeing books and the belongings of the people who at one time lived there. Again, tears were brought to my eyes, thinking of the loss and suffering. When we arrived, one of the locals ran up to us, shouting and waving to us and carrying an older gentleman on a homemade stretcher. He was not conscious. We immediately went to work and, after some time, we were able to revive him. That night after setting up camp, we sat around a fire with several local people who brought us food and sang folk songs.

Armed Violence in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

In 2018, I worked with International Medical Corps in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—just before the second Ebola outbreak—to conduct an assessment regarding the situation with internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the region. Due to the violence between armed groups, several thousand IDPs needed shelter and medical care.

Working with International Medical Corps’ local staff, the Ministry of Health and other international agencies, we were able to provide healthcare in the region. After my visit to the DRC, an Ebola outbreak occurred, and I worked as the response manager from the US with the team in the DRC on International Medical Corps’ response to this crisis as well.

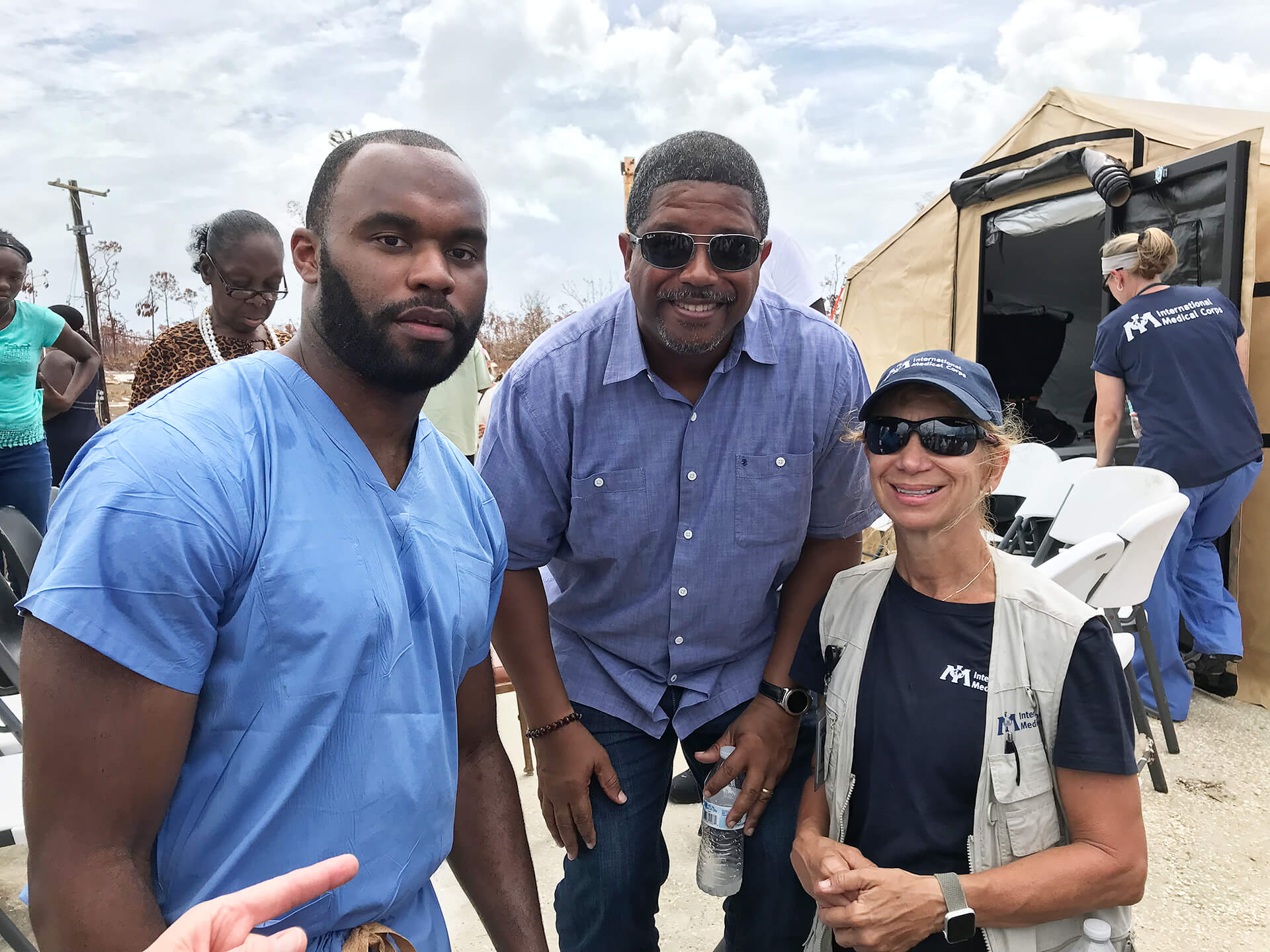

Hurricane in the Bahamas

In 2019, Hurricane Dorian—a category 5 hurricane—was recorded as the worst natural disaster in the history of the Bahamas and the most powerful hurricane in the Atlantic Ocean. We arrived on the island immediately after the hurricane, and I met with local, national and global partners to determine where International Medical Corps could provide the greatest assistance.

We conducted an assessment on the island of Grand Bahama, one of the hardest-hit islands. Parts of the island had been washed away, and we traveled house to house to provide input to US government agencies who awarded us a grant to set up our clinic. I’m always amazed at the resilience of those who suffer a catastrophic event.

One gentleman survived for hours clinging to a palm tree, in shock and unable to find his home. We later learned it had been washed away. Several clinics had been reduced to rubble, and we set up our outpatient clinic across the street from the destroyed building. On the first Sunday after the hurricane, local leaders held a church service at our clinic. They thanked us and sang in procession down to the ocean in gratitude for our service. Again, we were humbled.

COVID-19 and Hurricanes in the United States of America

Multiple crises, including hurricanes in Florida, Texas and Puerto Rico, and COVID-19 in NYC during the initial crisis in the hardest-hit hospitals in Brooklyn and the Bronx.

How do other responses compare to your New York City COVID-19 response?

That’s a great question, and I recall a response I had during an interview when I was in NYC for the COVID-19 response. I noted that, in a way, working in NYC during the first COVID surge when NYC was the epicentre was worse than some of the most difficult humanitarian crises I had experienced. I think it’s easier to process when it’s not your “home.”

While I had worked in the US during many other disasters, this was different. To a degree, I think we thought we could handle the pandemic; somehow, someway, we would manage. But we were wrong, the pandemic was not something anyone was prepared for, and when it hit NYC, it hit hard. I remember thinking that it wasn’t something that was supposed to happen anywhere, let alone in NYC. We were at a loss as to how to manage this pandemic.

We had no treatment, no way to stop it, no way to manage the deceased, and we lacked most of the things we needed—people, equipment and supplies. Thankfully, International Medical Corps was able to help with all of the greatest needs—people, equipment and supplies. Even with that help, the system was simply overwhelmed with a disease that we did not know how to treat or manage.

I remember one of the firefighters who helped us set up a surge capacity tent was chatting with me. He said he was one of the firefighters in NYC for 911, and as horrific as that was, this was worse. That was a shock to our nation, but with this pandemic, there was no end and no way to help.

No one was spared. Victims of the pandemic continued to come to the emergency rooms in ambulances, most in respiratory arrest or looking as though they would be very shortly. One time I counted six ambulances. I remember seeing an EMT performing CPR on top of the stretcher as they wheeled the patient off the ambulance. On another ambulance, another patient—ashen and gasping for air—was being transported into the already overburdened ER. And on the other side of the hospital, there was a refrigerated truck for the deceased.

I watched in shock as they were bringing patients in one side as they were wheeling them out the other side—first one, then two, then three and four refrigerated trucks for the deceased. They eventually had to shut down the street for the trucks. This was unimaginable and something I had never seen in the US or in most places in the world. It was a very difficult time for everyone.

While I was familiar with the intensity and tragedy and suffering of a humanitarian crisis, I think when it’s in “your backyard,” the impact is different. It reminded me of other horrific tragedies I have experienced with humanitarian work—while we are all very different, we are all very much the same. Part of what brings us back to this work is experiencing the best of humanity in a time of crisis.

What I saw in NYC and what I have seen across the world in any crisis—you can see the worst in humanity, but you can also see the best in humanity. Who you are and where you come from goes away, and people unite to help each other. It’s a gift in this work.

What does an overwhelmed healthcare system look like from your experience in USA?

The word desperate comes to mind. Desperate patients and families looking for care, desperate nurses, doctors and healthcare workers trying their best to save as many lives as possible, to give the best care they can while knowing it falls short of what they want to provide but cannot as there are too many sick patients to treat.

Desperate administrators and managers who have run out of options to provide the supplies, resources and staffing they know they need to keep everyone safe. There was a CEO of a hospital in tears, desperate for nursing help as they were so short of staff, many of whom were out with COVID.

The hospital had converted to a critical-care facility with so many critically ill COVID patients. It was truly shocking to everyone who was there, incredibly sad. It brings tears to my eyes today, thinking of how we were not prepared for this. I don’t think anyone could have been.

What advice do you have for health services in other countries that have not experienced what NYC experienced?

To learn from other regions. One of my mantras is to be prepared. While we were not prepared for this pandemic, and as I mentioned, I do not think anyone could have been—having a plan with respect to staffing, supplies and transitioning a facility to a high risk, acute care, or infectious disease setting is key. I believe we’ve learned from this pandemic. We’ve learned how to surge up an entire hospital to a critical-care facility, how to shift resources and supplies to serve as many as possible.

Training staff to be in a position to do this is critical. We needed more nursing staff with critical-care experience, and while it did not happen overnight, many nurses were eventually trained to help critical-care scenarios. Having a worst-case plan for medical students and residents to play a role was critical as well. It is truly no different than response work. We are always training—we train all of our staff and volunteers, not just the medical team.

Non-medical team members need proper training too. I can’t state enough how invaluable non-medical staff can be. The aides and janitorial staff in the ER and ICUs were doing their best to keep the areas clean and disinfected while protecting themselves as well. They also needed training to reduce transmission. While supplies are key, proper infection prevention protocols are critical to prevent transmission.

What advice do you have for nurses who are wanting to transition into the humanitarian space?

DO IT! It’s the most difficult but rewarding work you’ll ever do. I often have nurses ask, “Where do I start? How do I start?” I suggest they find a reputable organization by doing some research, then apply as a volunteer. You may start doing something more “mundane,” maybe a drill or giving injections initially, but you get exposure to the agency, learn their processes and culture, and before you know it, you’ll be on the roster and loving it!

What are 3 things you wish you knew before you started down the humanitarian route?

- How inspiring (and exhausting!) the work can be. I would have started it sooner if I knew how rewarding working in the humanitarian sector would be!

- Take time for yourself—the old adage of putting your oxygen mask on first holds true for this work. Most of us in the humanitarian sector have a hard time balancing work and life, especially when we’re deployed. I often work super long days (15+ hours), not because I’m asked to but because at the onset of a disaster, there is never enough time in the day to do what you need to do, and you want to do it all. The result is burnout. I have learned this the hard way and can’t emphasize rest and recovery enough!

- Find joy in the moment. I’ve had so many memorable experiences in this line of work. In Nepal, while digging out an area we were using for our clinic, an elder of the community came over and started helping. He wanted me to sit down and rest. I shook my head and pretended to flex my muscle. He did the same and pointed to me. We laughed until we nearly cried, then we went back to work. Those small moments stick with you and help form the person you become.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about humanitarian work, in your opinion?

That it’s always high intensity. It can be, but sometimes, it’s sitting and waiting for the local ministry to provide your assignment, or it can become more like an outpatient clinic, refilling prescriptions that were lost in the disaster or crisis, or you’re filling in for staff that is in crisis. These more mundane tasks can be difficult for medical staff who are expecting more of an intense experience, or it can also be the opposite. My feeling is, we are serving a purpose, and without us, they would not have the care we are providing. It’s all about managing expectations.

What are some final key lessons you’ve learned during your career as a nurse so far?

It is the most rewarding work you can do. It’s like life in many ways, some challenges, many rewards, and always learning and growing. The key is if you’re in a sector in nursing you’re unhappy with, change it. I have changed careers several times from hands-on nursing to working for a medical device company in product development and management to the humanitarian sector to consulting work. It is a field with so many opportunities and amazing experiences!

Extra Background information. How did you get into humanitarian nursing with International Medical Corps?

Hello, I’m Susan Mangicaro—many of my friends call me Sue! My story of how I got into working in the humanitarian sector goes back to 2010. I was working for a medical device company at the time and was involved in a project in China with people from multiple different organizations and agencies. We had a conference call scheduled for this project, and one of the members of the team, who was the founder of a small NGO in the US (and also an MD), sent us an email saying he was sorry he could not join the call. He was in Haiti with his medical NGO and said, “If anyone can come help, please call me.”

When I read that note, I immediately knew I was going to help. I had always wanted to work with a humanitarian organization, but I was a single mom and never felt I could take the time to fulfill that calling. But by that point, my son was in college. I sent an email to my colleague, and a few weeks later, with my employer’s support, I flew to Haiti on my first assignment. It was less than a month after that horrific humanitarian crisis, and my first impression when I finally arrived in Haiti (via ground transport from the UN through the Dominican Republic) was that of shock and devastation.

While I am not in the military, I could only guess that this was what a war zone might look like. All of the photos and videos did not begin to show the destruction or impact it had on so many in Haiti. I had not worked in the humanitarian/emergency response sector before. In hindsight, my experiences in this sector helped me to understand my purpose in life. When my time in Haiti was coming to an end, even after being away from home for weeks, I did not want to leave. I felt that what we were doing had a much bigger purpose than my corporate job.

I remember thinking how much I looked forward to returning home from holidays or vacations, whether a work trip to an exotic region of the world or a lovely vacation with my son. I always looked forward to returning home. Now, here I was in the middle of one of the worst humanitarian crises of our time, in very austere conditions, with little sleep and a high level of stress, and I wanted to stay.

This work, the opportunity to experience what we did helping those in need, was much bigger than life as we knew it on a daily basis, so much bigger than me. I thought this truly was what life was and is about—helping others, working as a team and banding together for the good of humanity. We bonded with the other volunteers, our translators, drivers and security, and most importantly, the recipients of the care we were delivering.

We became a family and worked together toward the same purpose, the same goal—to do what we could to make life just a little bit better for those suffering the most and to do something for someone without expecting anything in return. Even if it’s just to listen to someone’s story, or to hold a hand, dress a wound or comfort someone who lost a loved one—knowing that you may have helped them get through a day made this the most rewarding thing I had ever experienced.

Many would say how much they appreciated the help in words (through an interpreter), some in gestures and some with a smile. They often said how they felt they were forgotten, but our presence gave them some hope. And while I wasn’t looking for it, the reward was greater than I could ever have imagined. As such, I immediately fell in love with the work and knew this was my calling.

You must be logged in to post a comment.