Table of Contents

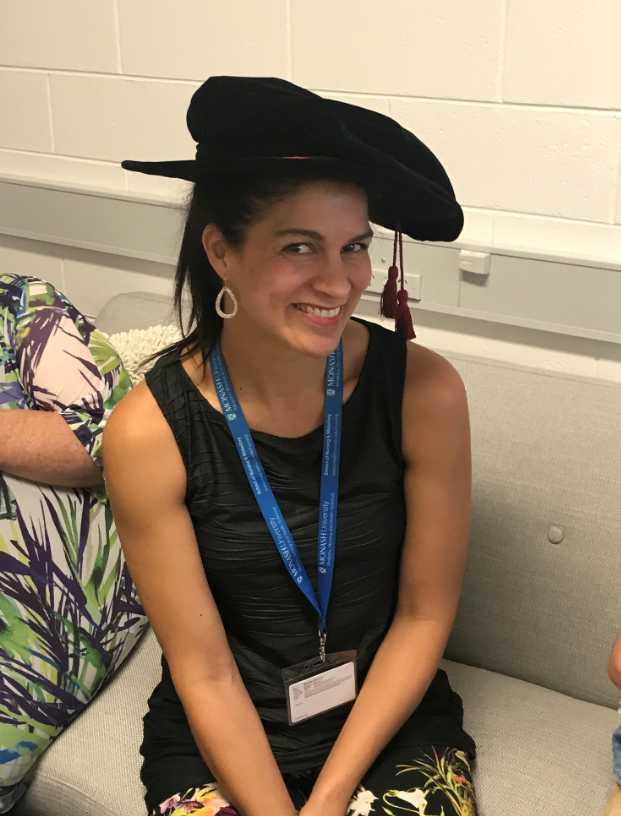

Meet Patricia Nayna Schwerdtle from Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF Australia)

- PhD Candidate, Heidelberg Institute of Global Health, Heidelberg University, Germany

- Adjunct Academic, Nursing & Midwifery, Monash University, Australia

- Vice President, Medecins Sans Frontieres, Australia

Trish is a climate change and health academic currently undertaking a Ph.D. investigating climate-related migration and health. Trish has worked as a consultant for Government, multilateral agencies and NGOs on Climate and Health. With a clinical background as an RN and experience in health professional education, Trish is currently the Vice President of Médecins Sans Frontières Australia and also conducts research on humanitarian assistance.

You have worn many hats so far in your career. Starting in emergency and intensive care in Europe including Holland and Germany and even as a medic in the Australian Defence Force.

You are currently reading PART 1 of our Q&A with Patricia. GO HERE to read PART 2 where we ask indepth about nursing and climate change, nuclear war and the role of the nurse within these issues.

Can you tell us about the start of your nursing career?

I completed my graduate year in the Emergency Departement, which was a rare thing at the time but I knew it was where I wanted to be. It was pretty overwhelming at first thinking anything could come in at any time and I was seeing patients with health issues I’d never heard of but I just loved the learning experience, the action and the team orientation of the job. I knew I wanted to travel as an ED RN so I did my Post-Grad straight after my Graduate year.

My role as Base Nurse in South Sudan was by far the most fulfilling job I have ever had. I’ve wanted to get back there ever since. I learned a great deal from highly skilled locally hired staff, and the nurses and midwives I worked with from Kenya and Liberia were truly inspiring. It was wonderful to see such great outcomes with such a modest input. For example, working in a therapeutic feeding centre, kids would come in flat and weak and emaciated slowly, with a mix of antibiotics, vitamins and therapeutic food you would see them get their personalities back.

It was really hard to work in ICU in Europe after that – the inequity was something I couldn’t reconcile. So, like many, that is when I got into public health, and later into international health, which evolved into global health.

Can you describe your transition away from clinical practice and onto research and public health?

I was getting to a point of saturation in emergency where I didn’t feel I was learning new things anymore and it was more about updating. I was also in senior management and it felt like I was always chasing other people to move the traffic through the ED. It still had it’s moments but became pretty administrative. I thought, I could either go from CNS/ANUM to NUM, or change lanes and get into academia. What really happened was that my sister bought me the book ‘Lean In’ and encouraged me to apply for a job I didn’t think I could do. I went for it, and I got it. Doors opened after that.

Image caption: MSF Primary Health Care Centre, Therapeutic Feeding Centre, Lankien, South Sudan.

What does a typical day look like for you currently as an academic at Monash University, PhD candidate and Vice President of MSF Australia?

Wow, good questions! Every day is really different.

As an academic at Monash, my role was beautifully balanced between research, teaching and service/leadership. So I’d work with teams on research projects at various stages: Conceptualisation, planning, data collection, analysis, write up and presentation and I supervised nurses doing research. I’d then design units, update them, lecture and run interactive workshops (‘flipped classroom’). I taught Global Health so it was fascinating exploring issues, research and practice implications with the next generation of nurses and midwives.

As Vice President of MSF Australia, there is always some kind of crisis happening in the world that we need to keep informed about. As a board, we develop strategy, ensure compliance and monitor the financial viability and legal accountability of the organisation. We also have heated debates about current humanitarian issues and are held to account by an association of humanitarians whom we represent. In practice, this is a lot of sitting behind a computer and talking to people, but virtually it’s as exciting, dynamic and challenging as a busy Emergency Department.

What makes MSF unique compared to other healthcare NGOs?

Médecins Sans Frontières is an international, independent, medical humanitarian organisation that delivers emergency aid to people affected by armed conflict, epidemics, exclusion from healthcare and natural disasters. MSF offers assistance to people based on need and irrespective of race, religion, gender or political affiliation. MSF go where other actors cannot. Our independence allows us to speak out when our teams witness serious acts of violence, neglected crises, or obstrucations to its activities.

What does MSF Australia look for when recruiting health professionals?

What MSF is really looking for is a commitment to humanitarian principles; humanity, neutrality, independence and impartiality. MSF is also striving to have a more diverse and inclusive movement. We are not looking for people who want to jump in and out of projects for their own benefit but rather meaningfully support teams and enable them to lead projects themselves. In all honesty, you are likely to learn more than you teach in your first assignment, especially from highly skilled locally-hired staff.

There is a great need for leadership skills, community engagement and cultural competence. The commitment to localisation is real as well as a genuine commitment to transfer power to local teams and address structural inequalities. Ideally, you will want to be a professional humanitarian and be aware of the issues impacting the effective provision of quality humanitarian assistance. The skills and experience you need to join an MSF team are on the MSF Australia website along with the current sought after profiles.

What pathway would you like to see the future of the humanitarian sector take over the next 10 years?

Every humanitarian and development professional would probably say they would like to see themselves out of a job. As an end goal. Very sadly, given the gap between humanitarian needs and delivery, changing demographics, rising inequality, unsustainable development and global environmental changes, I don’t think that will be the case this century. My vision for humanitarian assistance would be the delivery of sustainable assistance; that does not contribute to climate change and environmental degradation, that engages in meaningful community collaboration enabling community-led and owned responses.

I’d like to see a shift in power from international staff originating from high-income countries to locally hired staff in places where humanitarian assistance is actually needed and that decisions are made close to people in need of assistance. I’d like to see better nurse and midwifery representation at every level of leadership, management and governance and health care that is evidence based, patient-centred and continually improving, without doing harm.

You were the Chair of the Governance and Association Standing Committee for MSF Australia. What is governance and why is it so important in health and health leadership?

It’s good to delineate leadership, management and governance. All health professionals should be demonstrating leadership qualities in their practice; it’s about being accountable, evidence-based and thinking critically.

Management is more of an official title and is about the day to day running of an organisation e.g – ANUM, NUM. Governance work is done by boards and it is about forming strategy, ensuring compliance legal and regulatory, setting standards, understanding and mitigating risk and developing policy. When everything is going well, you don’t need a board much but during crises like Ebola or COVID19 the decision making is in overload and the stakes can be high. The board of directors steers and supports the executive who actually do the work to realize the strategy.

If you want to affect change in an organisation it’s really vital to understand these leadership roles at every level in health and how they interact with eachother, where the levers for change are and the bigger picture so you can influence the development of an organisation in a positive way and a way that ultimately benefits the people you serve.

What makes a good leader? What type of leader would you say you are?

A good leader engages in servant leadership. That is, rather than seeing themselves as at the top, they enable people to do their best work. They do this by inspiring them, rather than using a carrot or stick, by setting an example and having strong vision and values.

In the world today, I think there is a bit of a crisis in leadership where it has become about influencing rather than leading. This has led to the rise of populist governments. At the same time, there is a shift from citizenship to consumerism. This is a worrying trend. When I think about good leadership I think it also relies on good citizens in terms of an awareness of both roles and responsibilities. There is a need to have good communication mechanisms and to understand how change works.

Good leaders read a lot, are active listeners, build on others ideas, critically think and most importantly are reflective. They can admit they are wrong and show vulnerability. Good leaders surround themselves with people who critique them to improve them, rather than people who agree and praise them. They value diversity of thought. They realise, it’s not all about them and that in fact, they don’t matter that much at all.

There are lots of things I am, and I am not yet as a leader. I’m very evidence-based and task-oriented, maybe because I’m a nurse, maybe too much. Sometimes I need to focus less on the task and more on people. I don’t always say what people want to hear but what I think is right. I’m also willing to change my mind based on new evidence or a good, convincing argument and I enjoy being challenged.

What research have you done? What piece of research are you most proud of so far?

I am a global health academic so my research is about many health issues in many contexts – I have done research on the effectiveness of cholera vaccination, mentorship as a model to build capacity of health teams in LMICs, education research for teaching nurses and midwives about sustainable healthcare and the experience of Ebola survivors in order to improve public health responses.

For a few years now I’ve narrowed my focus on climate change and health – looking specifically at how and why people move in response to climate change and the implications for their health, in order to inform policy and practice. I’m most proud of a systematic literature review synthesizing 30 years of reseach on climate change and health and climate change and migration; looking at that nexus. It was a huge undertaking and has just been published in Environmental Research Letters.

What advice do you have for nurses interested in pursuing research?

Don’t just think about knowledge generation but also knowledge synthesis and translation. Prioritise the impact and practical application of your research for the benefit of people you collect data from. Don’t be afraid to lead it – just like nurses are the lynchpin of health systems they are well equipped to lead interdisciplinary research teams.

What is one thing you wish you would have known before you started your career in this field?

That B’s really do get degrees – although I always resisted that. That networks, unfortunately, still matter a lot. That there are lots of ways to get where you want to go and so little diversions don’t matter that much. Linked to that, the nature of a dilemma means that both options are probably pretty good.

What are some great resources that have helped you along the way?

The MSF clinical guidelines, Sphere Guidelines and my Oxford Handbooks of Accident Emergency Medicine and Public Health Practice have seen the most action over the years. Right now I am reading ‘The righteous mind: why good people are divided by politics and religion’. It’s made me understand what I saw happening to the next generation of students in universities.

I like to ‘check my thought bubble’ frequently with what I read to ensure I’m digesting a range of views and evidence. This is especially important in a world where your feed is tailored to what you want to see – leading to polarisation and an inability to engage with different worldvies ultimately meaning we are having fewer successful conversations.

Who are the 3 people who have been most influential to you and why?

They say you have three marriages in your life: One to your life partner, to your profession/work and to yourself. My husband has been the most influential person to me because he’s just very generous, kind, patient and clever and makes me want to be a better person and parent.

Aine Markham (Vice President MSF International) and Stewart Condon (Ex-President of MSF Australia) because they are really authentic and inspiring leaders and taught me a lot about governance.

You are currently reading PART 1 of our Q&A with Patricia. GO HERE to read PART 2 where we ask indepth about nursing and climate change, nuclear war and the role of the nurse within these issues.

Some of Patricia’s Recent Publications

Nayna Schwerdtle, P., Connell, C. J., Lee, S., Plummer, V., Russo, P. L., Endacott, R., & Kuhn, L. (2020). Nurse Expertise: A Critical Resource in the COVID-19 Pandemic Response. Annals of Global Health, 86(1), 49. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2898

Schwerdtle, P., Bowen, K. & McMichael, C. The health impacts of climate-related migration. BMC Med 16, 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0981-7

Schwerdtle, P., Morphet, J. & Hall, H. A scoping review of mentorship of health personnel to improve the quality of health care in low and middle-income countries. Global Health 13, 77 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-017-0301-1

2020: Nayna Schwerdtle, P., Irvine, E., Brockington, S. et al. ‘Calibrating to scale: a framework for humanitarian health organizations to anticipate, prevent, prepare for and manage climate-related health risks’. Global Health Vol.16. No.54.

You are currently reading PART 1 of our Q&A with Patricia. GO HERE to read PART 2 where we ask indepth about nursing and climate change, nuclear war and the role of the nurse within these issues.

Did you enjoy this Q&A? Make sure to subscribe for free HERE to The Nurse Break

Check out other Leadership & Management articles HERE

Check out other Humanitarian articles HERE

You might like our interview with the CEO of the Royal Flying Doctor’s Servcie (QLD) who is also a nurse!

You must be logged in to post a comment.