Table of Contents

The Nurse Break is fortunate to interview Duncan McKenzie R.N., R.M.H.N. who has many years experience working in both the public and private health system at various hospitals and clinics within Melbourne. Duncan is a Credentialed Specialist Nurse (Mental Health) in Australia, a Registered Mental Health Nurse with the UK NMC and a Certified Clinical Trauma Specialist with the Arizona Trauma Institute.

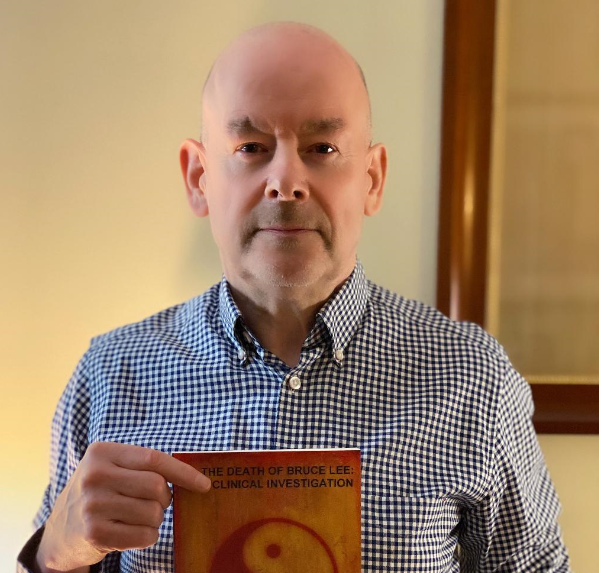

Some of his roles have included; CAT Team clinician, Psychiatric Triage Clinician and Associate Nurse Unit Manager. In 2010 Duncan took a 2 year sabbatical and lived in the Philippines, where he conducted research and wrote a number of books. These books include ‘The Death of Bruce Lee: A Clinical Investigation‘ and ‘The Near Death Experience: A Clinical Investigation’.

Use the content’s table above to navigate your way through this article as many different themes are coverered!

For other Mental Health nursing articles go HERE

General Mental Health Nursing Questions

What motivated you to become a Nurse?

At the age of 18 years, I was like many others and really didn’t know what I wanted to do. I did have a sense of wanting to do something useful and rewarding and both my parents worked at a local hospital called Fairfield Hospital in Bedfordshire, UK. I had never thought of becoming a nurse, however my mother, seeing that I was at a loss as to what to do career-wise, brought me some information on undertaking Registered Mental Health Nurse Training at Fairfield. The hospital was completely self-contained and had its own training school. It has since been decommissioned, as was the fate of the other large institutions of that time. This was in 1973, in the days of hospital-based training.

Fairfield Hospital Training School 1973

I completed the necessary entrance examinations, was accepted as a student nurse, and never looked back. We had superb nursing tutors and the hospital physicians and psychiatrists gave us our medical and psychiatry lectures. Plus, everything that we studied in the training school was something that we could see in that huge hospital when we had our placements rotating around the wards.

For instance, in a medical lecture, we might be told by the doctor about Huntington’s Chorea, who would then say, “If you are rostered on ward M8 you will see a patient suffering from this condition.” And then if we were placed on that ward we would see patients suffering from this dreadful condition and be engaged in their nursing care. There was such an immediate link from the theory of our training school to our practice and experience on the wards.

What pathway’s and experiences lead you mental health nursing?

In 1973, when I started my training, we had the two streams of General Nursing and Mental Health Nursing. I took the undergraduate Mental Health Nurse stream. I was very interested in psychology and psychiatry, although its practice and theoretical parameters were very different then. As part of my mental health nurse training, I had a 3-month placement at nearby Bedford General Hospital and completed another year at that hospital after I graduated from my Mental Health Nurse course, doing general nurse training on the medical and surgical wards.

Again, that was another fascinating experience, but I kept feeling the urge to return to psychiatric nursing and that led to me transferring as a staff nurse to the Weller Wing, the mental health unit, at the Bedford General Hospital. Subsequent to that I emigrated to Australia in 1978 and have worked in psychiatry ever since.

What additional studies did you have to do in order to become a Mental Health Nurse?

In those days the 3-year mental health nurse training was the specialist nursing course, and the pathway was unlike today where one completes an undergraduate RN course and then specialises with post-graduate training. Since my graduation, I have engaged in a large amount of continuous further study and training and I am a Credentialed Mental Health Nurse, which recognises my status as a specialist nurse.

I am also a member of the Australian College of Mental Health Nurses and I believe that the membership of our specialist organisations is critical for allowing the dissemination of knowledge and policy, and indeed for determining the direction of policy through effective representation and political engagement.

Student of the Year Prize at Fairfield circa 1975

What is a typical day for you as a mental health nurse, what are some of your key roles and responsibilities?

The role of a mental health nurse varies tremendously, depending on the setting that one is working in and the degree of one’s education and experience. Regarding my own situation I am employed by the Swinburne University of Technology and, along with other mental health nurses and a team of health professionals, look after the mental health needs of the student population and staff.

My principal role is that of a counsellor / mental health clinician and our Counselling and Psychological Services team look after the students from a mental health point of view. In my practice of counselling, my main areas of expertise and interest are cognitive behavioural therapy, hypnotherapy and the treatment of anxiety disorders.

What are some of the most difficult and rewarding aspects of mental health nursing?

Working in some areas of the mental health sector can be extremely challenging and demanding. Just to take only one example of an acute mental health in-patient unit where one may get individuals admitted who are experiencing the florid symptoms of drug-induced psychosis. Such individuals are likely to be completely insightless regarding their condition and not able to form a ‘therapeutic alliance’ in any form.

Of course, it is tremendously rewarding to see such an individual settle and become asymptomatic, however, the scourge of substance abuse in our society often means that they do relapse on engaging in further drug abuse. The nature of the substances used nowadays can leave marked personality and cognitive changes within the individual so that they display on-going psychosocial deterioration. The rewards, of course, relate to seeing individuals get better, become asymptomatic and move on with their lives.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about mental health nursing?

Despite being concerned with psychological processes the mental health nurse must have a solid grounding in anatomy and physiology and medical knowledge. The reason for this is that our emotions and behaviours are of course mediated by the brain and by the central nervous system.

This understanding is especially valuable in the case of psychological trauma and PTSD, where the underpinning of psychological intervention is based on a thorough understanding of the brain and its structure and function. When one treats anxiety disorder it is essential to understand the autonomic nervous system and concepts such a sympathetic dominance of the autonomic nervous system.

When I recently completed my Clinical Trauma Specialist training the foundational concepts of PTSD and its treatment-related to neuroanatomy, with brain structures such as the amygdala, the hippocampus and several regions of the prefrontal cortex playing critical roles in symptomatology. There is also a large body of knowledge that relates to brain function and dysfunction regarding neurotransmitters and their role in psychiatric pathology.

And so, one’s psychological interventions, to be effective and evidence-based, must reflect such contemporary knowledge that allows us to understand what is actually happening with the organic structures that mediate the symptomatology. The other reason why mental health nurses must have a good understanding of physical pathology is to understand the difference between a functional and an organic presentation.

So, what is the difference between a functional and an organic presentation?

It is critically important that a nurse understand and be able to recognise the difference between a functional and organic presentation. It is the capacity to discern the difference between, for example, the functional disorganisation of behaviour in psychosis from the organic syndrome of a delirium. It is a skill that is honed with training and experience. The disorganisation of the behaviour of a psychosis or the dissociative states that we see in conditions such as PTSD is not the result of underlying acute medical conditions such as altered metabolic states, acute alcohol or drug withdrawal, or the consequences of progressive, insidious frontal lobe damage that occurs in the aforementioned condition of neurosyphilis.

This is the critical area in which we work with our medical colleagues and refer the patient for an organic screen to rule out organic states that we may consider as a differential diagnosis. I do remember for instance, in my role as a psychiatric triage clinician, I was asked to psychiatrically review a patient who was ‘psychotic’. It took me only a short while to determine that the patient was in a delirium and I referred him immediately to the medical staff. This constituted a medical emergency and I had no further role to play.

Can mental health nurses be ‘qualified’ or upskilled in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT), hypnotherapy and so on?

I could talk for hours about this but in view of our time constraints let me answer as succinctly as I can. From our Registered Nurse Standards of Practice, we are advised that scope of practice is that in which nurses are educated, competent to perform and permitted by law. The actual scope of nursing practice is influenced by the context in which the nurse practices, the health needs of patients, the level of competence and confidence of the nurse and the policy requirements of the service provider.

I have worked in a variety of clinical settings, from wards managing patients with chronic illness, acute admission wards, to being a CATT clinician, a psychiatric triage clinician and in my current role as a University mental health nurse/counsellor. The way in which I practice as a nurse has varied enormously over my career, depending on the context in which I am working and my skills and education at that time. Continuous professional development allows us to study and learn new modalities, this is its purpose and intent.

To answer your question ‘Can MH nurses be ‘qualified’ or upskilled in CBT, hypnotherapy and so on?’, the answer is, ‘Of course they can!’

In the context of a mental health nurse working in a generic counselling role, CBT and hypnotherapy are commonly used, safe, effective and evidence-based treatment modalities. However, in other mental health nurse practice areas, they may not be relevant or indicated at all, or the nurse may not have the clinical autonomy that allows this.

Hypnosis has a strange regulatory history. Prior to it becoming completely deregulated in Australia the only professions that could practice hypnosis were Doctors, Psychologists, psychiatrists, ministers of religion and dentists. Fortunately, this nonsensical legislation was scrapped some years back. Now ANYONE can practice hypnosis. Part of the problem around this particular topic is people not understanding that hypnosis is a completely natural and common phenomenon. Some of the best hypnotic states I have seen is when walking through a casino and watching habitual gamblers play the slot machines.

They are in a very effective state of trance. That’s a bad side of hypnotic phenomena. Of course, we use hypnotic techniques for therapeutic ends, helping the patient through guided imagery training, auto-suggestion and positive belief affirmation to manage symptoms and control behaviours that are maladaptive. But beyond using it for therapeutic ends I would recommend the study of hypnosis to every mental health nurse, as it allows significant insight into the way we our behaviour is influenced by others and how we can effectively influence others for therapeutic ends.

Some of the best hypnotists on this planet are not clinicians but salesmen, politicians and those in advertising. They understand the patterns of language and communication that influence human behaviour, induce trance states and lead individuals towards specific goals. The only difference with we as clinicians is that our only aim is a therapeutic outcome and not commercial gain. The critical point is that the nurse applies their knowledge and skills strictly in the context of their established ethical framework and with a focus on effective clinical outcomes.

When it comes to CBT, Hypnotherapy, Gestalt Therapy and all the other plethora of therapies I can also tell you something that may surprise you. It is not the technical knowledge about specific therapies that are the most significant factor in therapeutic outcomes, but the rapport and effective communication initially established by the therapist. It is not so much a case of ‘How good am I at Cognitive Behavioural Therapy’ but ‘How good am I at relating to my patient, understanding them and instilling in them a sense of empowerment, hope and control?’ It is only after those initial conditions are established that the ‘technical’ side of treatment, such as CBT interventions, can be applied optimally.

What advice would you give to nurses to best overcome mental health stigmas in our patient care?

Fortunately, nowadays we are talking more openly about mental health issues, and this progress has been helped by prominent individuals within our society talking about their own struggles and mental health problems. We do need to be open in our discussion of these issues and to challenge maladaptive societal expectations of how we manage emotions and how we react to mental illness.

How do you deal with the stresses of your job?

The critical issue here is the support one receives from one’s colleagues at work. Fortunately, at my current workplace at Swinburne University, we have a great team and a very supportive culture. It is always easy to discuss issues of concern to other team members and to feel validated and supported. In every workplace, I venture to say there is going to be some degree of stress and problematic issues. It is not that such stress exists but how it is dealt with and with supportive colleagues and management.

How vital are CNS or CSN’s in the mental health sector? How would you encourage more to peruse this?

The Clinical Nurse Specialist and our contemporary career structure are designed to advance nurses who have skills and experience in their chosen speciality. Usually, within the ward setting, they will have a specific portfolio of interest and be considered clinical leaders and role models. Focusing on such portfolios of speciality allows for nurses to advance their clinical skills and knowledge and to be considered advanced practitioners.

Do you think more emphasis should be placed on a thorough mental health assessment by all nurses?

This is absolutely critical. In my view, there are certain core functions that a nurse of any speciality should be able to perform. One is a physical assessment, the other is a mental state assessment. Further to this, as an adjunct to mental state assessment, a capacity to perform at least a basic risk assessment is also essential. The assessment, treatment and care of patients in a holistic sense demands the above.

How would you empower more nurses to have the confidence to broach mental health illnesses and disorders with their patients?

Where patients do have problems, the vast majority will want to unburden themselves and will be happy to receive support and guidance. Others may feel embarrassed or the issue of stigma may be a barrier. In such cases, an open invitation to talk at a time they feel comfortable can be given. For nurses who do not have a great deal of experience in mental health issues the capacity to engage in secondary consultation would be useful and this is why as nurses and as health professionals within a multidisciplinary team we need to nurture and maintain professional linkages, networks and resources.

How has mental health nursing / the sector changed in your time?

The changes in my lifetime and in my career have been enormous. As a nurse, one is dealing with diagnoses and with interventions that one does not see anymore. Let me give you some examples. In 1973, when I started my training I was caring for patients who had a diagnosis of neurosyphilis, which would be extremely rare nowadays. I was also engaged in the care of patients who had undergone psychosurgery, such as lobotomy.

As an investigative procedure doctors also used an old method called abreaction where the patient was put in a state of twilight consciousness using Sodium Pentothal for instance. The theory was that certain mental health problems were caused by repressed memories which needed to be dealt with consciously. An individual in this twilight state would be able to ‘let go’ of these memories and often underwent an emotional catharsis.

Such was used also for patients with ‘shell shock’, what we would refer to nowadays as PTSD. Certain patients and cases do stick in one’s mind and I do remember one male patient who was admitted to the ward in an acute state of mania with elevated mood and so on. After a few days, the Registrar decided to perform abreaction with this patient and I was present as the nurse to assist. During one of our training school sessions just prior to this event I had been learning about the various psychodynamic theories of mental illness and we were told of one British psychiatrist of that era who believed that mania was ‘a flight from depression’.

Interestingly, during this abreaction, the patient started relating all manner of depressive themes and experiences and began crying. That appeared to be, anecdotally at least, some confirmation of that theory. Further to that theory we do of course have the biochemical theories of mood disorders. Working as a nurse in the last century, starting my training in 1973, one can see very clear changes that have taken place regarding our role.

The roles of clinicians were very strictly demarcated, whereas now there has certainly been a blurring of clinical roles and responsibilities. For example, the role of nurse prescribing and how that was initially resisted by the medical profession. This kind of ‘turf war’ was non-existent in the days of my training.

There was unremitting respect by the medical staff towards nurses and vice versa, and very clearly demarcated parameters in which one practised. Change has come about due to the unrelenting process of specialisation and due to the explosion of knowledge and information that we have now. Further to this, greater accountability and the practice of defensive medicine has increased exponentially, to the point where the behaviour of nurses and of doctors is partly driven by the desire to avoid litigation. The situation has reached something of a crisis point in the United States where malpractice insurance is a huge cost and burden on clinical professionals.

How do you think this sector can better function and better care for its patients?

The mental health system is under huge pressure. There are far greater expectations from patients and their families as to what can be achieved. There is far greater scrutiny of the way we work, greater oversight and governance, and greater attention to the errors that are made. There is exponentially greater complexity in everything that we do. Sadly, I cannot see any reversal of this and resources are always going to lag demand.

Associate Nurse Unit Manager

Where were you an ANUM, how do you become one and what do they do?

I have previously worked as an Associate Nurse Unit Manager in two private hospitals in Melbourne over a time span of approximately 8 years.

The associate nurse unit manager is a nurse whose training and experience identifies them as having the skills to effectively administer a ward, manage staff and provide their own clinical input into patient care. In order to perform this role adequately one must have the necessary training and experience.

The ANUM is effectively a shift leader who is responsible for the direct oversight of the ward and the staff and patients therein. The allocation of resources, the supervision and oversight of staff, advanced clinical input into patient’s care and a leadership role are part of the roles and responsibilities of an ANUM. The ANUM is directly accountable to the Nurse Unit Manager in terms of line management.

What are the challenging aspects of being an ANUM ad what qualities make a great manager?

Direct responsibility for the running of the ward, often outside of office hours when other staff are not immediately available, can be challenging. Personally, I have been an ANUM on night duty, where one has limited resources and personnel to call on. The capacity for clear thinking, good leadership skills, excellent standard of clinical knowledge and the capacity to be an effective role model are some of the necessary attributes. The latter especially so if one has nursing students on the ward.

Clinical Trauma Specialist and CAT Team

What does it mean to be a certified Clinical Trauma Specialist?

Clinical trauma in this regard refers to psychological trauma in my own speciality of mental health. As a specialist mental health nurse who engages in psychotherapy and counselling, it is critical to have knowledge about PTSD and other emotional trauma-related disorders. It is important for clinicians to understand that childhood emotional trauma and lack of secure attachment in the developmental years can transform into a whole range of psychopathology in the adolescent and adult years.

The use of the ACE instrument, the Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaire, for instance, delineates this. The consequences of psychological trauma include, for example, substance abuse and chronic self-harm behaviour. I completed a course that was run by Dr. Eric Gentry to become a clinical trauma specialist. I then applied to the Arizona Trauma Institute for certification and after registering my mental health nurse credentials with them and completing an online examination on clinical trauma I was certified with this organization to practice clinical trauma interventions.

What would a typical day look for you in this above role?

Emotional trauma and its treatment is incorporated into my daily role as a counsellor / mental health clinician. Currently, I am working with students who present with some form of mental health issue and it is my role, with the rest of the team, to provide support, intervention and treatment to this individual. The style of engagement, when we are presented with individuals who have suffered emotional trauma, is called trauma-informed care.

What does CAT stand for and what does a CAT team nurse do?

The Crisis Assessment and Treatment Team is a multidisciplinary, community based mental health team whose focus is to assess and treat those with acute mental illness in the community as an alternative to hospitalisation.

The mental health nurse has specialist skills and within the CAT team, their expertise is evidenced in areas such as medication management, psychiatric assessment, physical assessment and psychological interventions. The team leader is a consultant psychiatrist and psychiatric registrars will form part of the clinical team, along with social workers, psychologists and occupational therapists.

Essentially, we would manage and treat individuals in the community where acuity of symptoms determined that crisis intervention was required and where the degree of risk was assessed by the CAT clinicians to be manageable.

What would be your advice to health care professionals caring for a patients with acute mental health issues?

Patients with acute mental health issues who present to ED would follow the usual pathway regarding medical review and assessment. They would initially be seen by the ED triage nurse who would determine the acuity of their presentation. The patient would then be assigned to an ED physician who would be responsible for the initial assessment of the patient.

Where it issues relating to the presentation were primarily of a mental health nature the ED physician would then initiate a referral to the psychiatric triage clinician whose duty it is to cover ED in terms of assessment of mental health presentations. In some health networks, the psychiatric triage clinician is an integral part of the CAT team and they are called to assess in ED, or it may be that the psychiatric triage clinician has a dedicated, ED-based role.

I have previously worked in the role of psychiatric triage clinician and I was responsible for the assessment of mental health presentations to ED and for the subsequent follow-up pathway and this would include referral to CATT, admission to the psychiatric in-patient ward, or referral to another community-based agency for follow-up. The psychiatric triage clinician has a lot of responsibility and clinical autonomy and they would be supported in their role by an on-call psychiatric registrar and an on-call consultant psychiatrist.

What criteria must be met for a CAT team assessment? How do nurses know to escalate for further mental health advice?

The acuity of symptoms and degree of risk determines the engagement of CAT. The majority of mental health presentations, such as depression, for instance, would be managed via General Practitioners. It is where the presence of acuity, complexity or risk requires immediate and specialist review that CATT provides a role in the provision of specialist assessment and community management.

Personal interest

As an author please elaborate on some of the work that you have done?

In 2010 I took a 2-year sabbatical and went to the Philippines to engage in writing and research. I wrote a few books including one on the near-death experience. I looked at this phenomenon from a cross-cultural and comparative point of view to determine whether there were specific cultural factors that influenced the near-death experience. I was able to travel into some remote communities in the Bicol Region of the Philippines and studied some fascinating folklore and mythology there. It was at that time too that I read a book written by Tom Bleecker called ‘Unsettled Matters.’

It was an attempt to explain the sudden death, at the age of 32 years, of the Kung Fu superstar Bruce Lee. The reasons for Lee’s death, as expounded in the book, didn’t make sense to me and so I determined to do my own research and I subsequently published a book called ‘The Death of Bruce Lee: A Clinical Investigation.’ A few years ago, the American author Matthew Polly began writing the definitive biography on Bruce Lee which became a best seller called ‘Bruce Lee A Life’. Matthew read my book during the research for his book and I contributed to his book regarding the causes of Lee’s death and being referenced there. It is always rewarding to see one’s work and research recognised.

What other interests and hobbies do you have?

I have a wide range of interests. I really enjoy riding my bike. I studied German for some years and I enjoy reading in German and watching German movies. I have also completed some historical research on the second world war, and researched the health and medical issues of Adolf Hitler, using documents in the original German. I had an article outlining that published in the ANMJ – ‘The Nurse as Amateur Forensic Researcher’. I have a great interest in Astronomy, and in radio communications. I have an advanced amateur radio licence issued by the Australian Communications Authority and am a radio ham, callsign VK3DRX.

Why do you think it’s important for nurses to have other interests?

It is critically important to have a balance in all that we do and an opportunity to shift perspective on all matters. The profession in which we are engaged in is demanding and complex and we need time and space to decompress.

As mentioned before, one has to remember that the complexity of the work that we do nowadays has increased exponentially. Not only the complexity but our accountability and the scrutiny we are put under has also increased. I am fortunate in that I work 0.8 EFT which provides the necessary time to decompress, engage in one’s hobbies and engage in on-going study outside of one’s day to day professional nursing practice.

What are your tips for nurses during this pandemic to manage the stress of their work and lockdowns?

The work that nurses are doing is absolutely critical to the health and wellbeing of our nation. Along with our medical colleagues and paramedics, there is no other group of professionals so intimately involved in patient care. During this pandemic, I look at my nursing colleagues, the general nurses who are managing patients in hospital settings with the known attached risk of contracting Covid-19 themselves, and my mental health nurse colleagues who are caring for individuals who are psychologically impacted and some who are suicidal, and I am I awe.

This pandemic will pass, but the memory of how our profession responded will be with us always. As in every previous disaster, conflict and emergency, our profession has risen to the occasion and performed exceptionally. It will do us well to remember this.

If I was in charge of nursing in Australia and could change anything, I would change…..?

An interesting question and I would answer it by firstly stating that my view is there is so much that is right with nursing and we do not need to change in any radical sense. We are a highly respected and trusted profession, in fact, polls year after year show that we are THE most trusted profession. We have expanded our clinical skills to the point where Nurse Practitioners routinely prescribe medications and diagnose, which would have been inconceivable in the UK when I started my training in 1973.

I always consider my hospital-based training to have been enormously valuable for the reasons I have outlined in previous questions, however, the amount of knowledge that we must learn now, and our professional status, demands a university-based education and so there is no going back to the hospital-based training modality. Overall, in my view, we have done a very good job of moving the profession forwards and remaining highly skilled, highly respected and adaptable. However, we do need to be ever-vigilant in protecting our interests as a profession and use whatever resources and power we have to protect and forward our own interests, just as every other profession does.

You must be logged in to post a comment.