Table of Contents

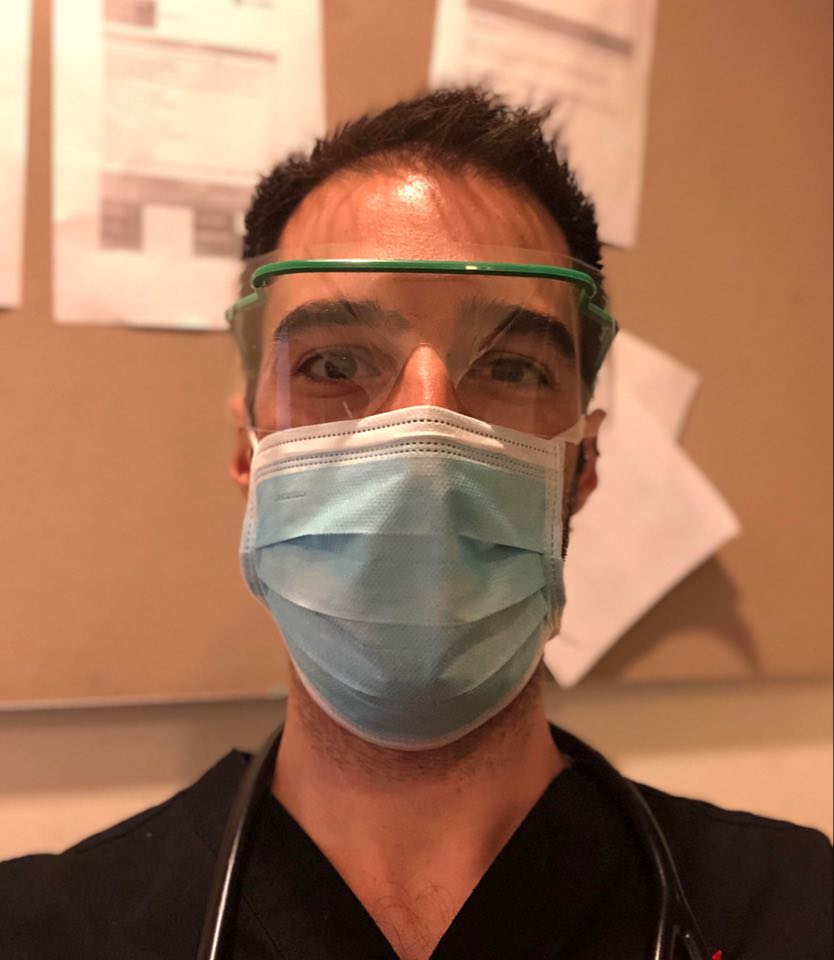

Dr Scott – Intensive Care Registrar

An AUSMED Australia and The Nurse Break collaboration brings you this scrolling feed of stories from those on the frontline of the health service! Check out Ausmed’s feed here. Want to be featured here? GO HERE to learn more

The changes in ICU since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic largely mimic those throughout the rest of the Australian hospital system. We have restructured our unit to physically separate confirmed, suspected and non-COVID patients, become much more meticulous with PPE, avoided aerosol-generating procedures, increased staffing levels and written innumerable new infection prevention protocols.

Much has been made in the media about creating and staffing additional ICU beds and manufacturing more ventilators to avoid the unthinkable situation of having to “decide who lives and who dies.” Whilst there’s no argument that people unlucky enough to suffer severe COVID-19 need intensive care, we now know that it’s not a panacea. Most studies from around the world have suggested that the mortality rate for patients with COVID-19 who require mechanical ventilation is >50%. Knowing that even the most resourced health system won’t be able to save everyone, it is therefore critically important not just to ‘flatten the curve’ but to minimise transmission and case numbers as much as is humanly possible.

Fortunately, after the initial flurry of activity preparing for what was anticipated to be an unprecedented public health crisis, we have now seen our ICU become eerily calm. The sudden surge in resources means patient to staff ratios have never been so good. Whilst no-one would want it any other way, we’ve been left in the awkward situation of being publicly lauded for doing our jobs with more support than ever before. The battle against COVID-19 is clearly far from won in Australia, but whilst so much of the rest of the world’s ICUs are still in the throes of battle, it’s hard not to have some survivors guilt.

Whilst there will no doubt be a gradual return to normality over the coming months (like the recent resumption of some elective surgery), with any luck some of the changes will stick. Hand hygiene compliance is the best it’s ever been, hospital administrators are thinking more about frontline staff wellbeing, Hospital in the Home programs have expanded and many inefficient meetings have been moved online or scrapped altogether. From a clinical perspective, it’s amazing how quickly COVID-19 has cleansed some practices from our repertoire that were long overdue to be retired.

For example, as part of efforts to reduce the number of staff exposed to aerosols during intubation, all of a sudden we find ourselves acknowledging that having an extra person in the room to provide cricoid pressure or manual in-line stabilisation isn’t necessary. For fear of touching our faces with contaminated equipment, suddenly everyone is much more willing to admit that stethoscopic auscultation adds little to the examination of most ICU patients. Most surprisingly perhaps, it seems overnight we’ve finally developed the willpower to limit the number of people in the room during a code (not to diminish the value-add of that 8th junior doctor who insists on getting involved during an arrest on the ward!).

COVID-19 has changed the Australian healthcare system enormously. We prepared for a disaster on a scale unprecedented in any of our living memory. By virtue of our geography, demography, adherence with social distancing, good contact tracing and probably luck we have thus far avoided disaster. The truth is no-one knows what the coming months will look like, but we must all try and learn from the experience to make a safer and more robust system going forward.