Table of Contents

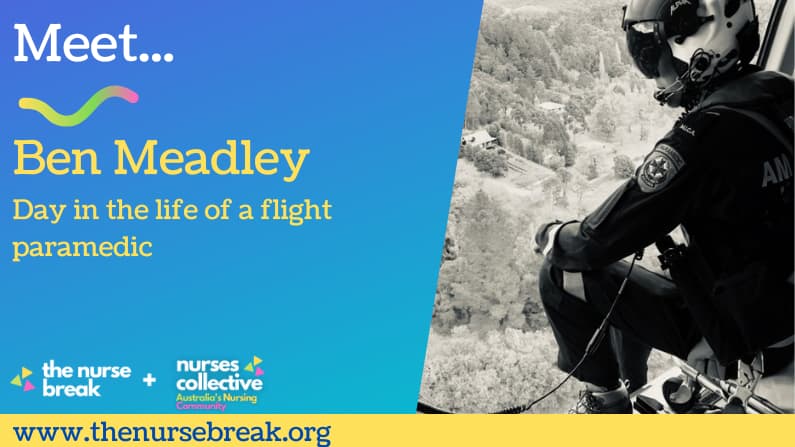

Please to have Ben Meadley write for The Nurse Break. Ben is a MICA Flight Paramedic (MFP), adjunct lecturer and Phd candidate. Enjoy!

Little introduction about you

I grew up in inner east Melbourne, worked as a paramedic in Sydney for just over 4 years, and now live in South Gippsland, VIC.

I’m a keen cyclist, with most riding these days in the hills of South Gippsland and surrounds. I play music, seek adventure with my wife and kids, usually in the bush or the beach.

I chose paramedicine as a career as I respected the humility with which paramedics went about their work, although that has changed nowadays. I also wanted to extend my knowledge of the human body in an applied setting, where I also had the opportunity to help people every day.

Did you have a career before you started paramedicine?

I was destined to be an exercise/sports science researcher after I completed an exercise science degree. However, I wanted to be out in the field, and was attracted to paramedicine after other’s from my degree applied to the role.

Where did you do your training?

I completed my undergrad exercise science degree at Victoria University in 1998, Diploma Paramedical Science at NSW Ambulance in 2002, Grad Dip Intensive Care at Victoria University in 2003, Grad Dip Emergency Health at Monash University in 2005, Grad Cert Emergency Health/Aeromedical Retrieval at Monash University in 2009, and will complete my PhD at Monash University in 2021.

I completed Intensive Care Paramedic training twice. Once whilst I still worked in NSW, then shortly after I moved back to Melbourne, where I completed the Grad Dip Emergency Health at Monash University to qualify as a MICA Paramedic in Victoria. Both programs offered unique perspectives on emergency prehospital critical care.

Where do you currently work?

I currently work at the HEMS 2 base at Traralgon in the Latrobe Valley, where I have been since 2013. Prior to this I worked at HEMS 1/HEMS 5 at Essendon Airport, Melbourne from 2009-2013.

What are the main types of patients you see in your current position and what is your role in their care?

As a MICA Flight Paramedic (MFP), our work is quite varied. MFPs are the solo clinician on the aircraft (the average prehospital experience of a MFP is 22 years). We are accompanied by the pilot (obviously) and an aircrew officer (ACO), who has extensive training in managing the medical equipment, similar to an anaesthetic technician.

Approximately 50% of our work is primary response, i.e. responding to roadside accidents, sporting and recreational accidents (my kids will never have a horse nor a motorbike), and in-field medical emergencies such as AMIs requiring thrombolysis, stroke patients requiring transport to endovascular clot retrieval facilities, or neurological emergencies requiring critical care. Our role has an increasing amount of medical work, with trauma decreasing in general.

This is great in my opinion, as we have can have an enormous impact on regional patients suffering cardiovascular or neurovascular emergencies.

Approximately 40% of our work is interhospital critical care retrieval. Where I work in Gippsland, there are many small Urgent Care Centres and Regional Eds that have no ICU or HDU, and they may not have emergency physician or anaesthetic coverage.

As such, we will often be sent to remote facilities to transfer critical care patients to higher levels of care, and reasonably frequently, we will be the senior clinician at these cases. We work very closely with regional nurses. This is especially the case at Urgent Care Centres where there may be no physician available at all.

For complex interhospital cases, a retrieval physician may accompany the MFP from an Essendon-based aircraft. For neonatal and paediatric critical care retrievals, a PIPER specialist physician and nurse will usually accompany the MFP, although we do complete quite a number of non-neonate paediatric transfers without a medical escort.

The other 10% of our role is as a rescue paramedic for search and rescue cases, where we may be winched into the water or remote overland areas to rescue sick or injured persons. All MFPs are trained rescue swimmers, and this fact alone can inhibit an applicant’s progress through the selection process. We have no doubt missed out on having a number of excellent paramedics work in the role because their swimming ability is not at the standard required, but it is an essential requirement. Although that type of work is less common, we can be called on at any time to perform this role.

Overland rescue by winch recovery is quite common, and increasingly so, with an ever-expanding population seeking recreational adventures in remote and difficult to access areas. The vast majority of patients rescued via winch from land are suffering isolated orthopaedic injuries, and just can’t get out from where they are. The base I work at performs nearly 60% of the winch rescues for the state, due its location close to Bass Strait and the Victoria’s alpine wilderness.

What is an example of a ‘day in the life’, and tips for others in your field?

We can be very busy or very quiet, it’s unpredictable and highly variable. We work a 10/14 roster (2 x 10hr days, 2 x 14hr nights, 4 days off) which can be taxing after over 20 years of 14-hour nights.

A typical dayshift would include:

0630: Arrive at the base, shower and prepare.

0700: We will let the nightshift sleep as late as possible, as they will either be on their first day off, or between nights, and the base is set up the maximise rest opportunities. This is especially important for the air crew, as there are legislative safety requirements surrounding rest and flying.

The dayshift pilot and ACO will check all the “flying bits” of the helicopter, I will check all the medical gear and search and rescue equipment. Then, the ACO and I will check the restricted medications in the safe and portable bags as per standard procedure that all nurses would be familiar with. We would usually go through a piece of infrequently used equipment at this time.

0800: The pilot, ACO and MFP gather for a weather brief from the pilot. We are often limited in our ability to fly due to weather, and fog is a big issue where I work, as are the nearby mountains when there is low cloud. We also check on each other’s currencies in aviation and clinical elements of what we do. It would be unusual to not have 2 or 3 training currencies to complete (e.g. winch currencies every 6 weeks (a practice winch), paediatric RSI accreditation, online clinical or aviation learning modules, navigation currencies for pilot and ACO, and the ACO has their own set of clinical currencies with regard to all our equipment that they must complete on a 4 month cycle). We may also have student MFPs in training who require devoted time and focus.

0900: If no job or training, then we often gather for coffee and quiz, then off to get all the training done either together or separately.

10-1700: It’s unlikely a job won’t come in, but if it doesn’t, we may go to the on-base gym as part of our requirement to maintain a physical standard for search and rescue work, complete some reading or other clinical training, local ambulance crews will come to debrief jobs or talk through some clinical concepts, order stores, put stores away, general base tidying, aircraft and equipment cleaning. There’s always something to do.

Inevitably when we do get a job, it takes us over the end of our shift. Each job takes 3.5-6 hours by the time you’ve responded, arrived, managed the patient, transported to the receiving hospital, handed over, completed paperwork, often we then fly to Essendon Airport to get fuel, then fly back to the Latrobe Valley. (Whilst the flying may sound exciting, it wears off pretty quickly when you’re a passenger.

The Latrobe Valley power stations and coal mines lost their appeal a long time ago, and helicopters can be very twitchy and uncomfortable in turbulence and strong winds). It would be more common than not for me to wander in the door at home 3-5 hours late after a day shift, with everyone at home long in bed. Sometimes you don’t get home at all, and I’ve spent nights in Launceston (after a water rescue on the north coast of Tasmania) and Canberra (after a job on the NSW border where Canberra was the nearest major trauma facility for a critical trauma patient). When the pilot “runs out” of legal hours to fly, that’s it. You stop wherever you are.

If you’re on your first dayshift and you finish anywhere after 730-8pm, it’s barely worth going home, as you have to be back at 0630 the next morning. All the other MFPs at my base live in Melbourne (this has to do with the experience base needed to gain a position), so they’ll stay between their dayshifts.

In saying that it can sometimes be quiet, that’s generally not my life.

In my last eight shifts, I have attended a multi-casualty car accident with two critically unwell patients requiring prehospital anaesthesia, blood, ultrasound, surgical thoracostomy; a very young person in a town near where I live in cardiac arrest post-hanging; thrombolysis for two separate STEMIs in the field: winched two patients from two different areas of Wilson’s Promontory over two separate shifts; transferred a critical ventilated GI bleed from a remote hospital to Melbourne, and a traumatic cardiac arrest on a major highway requiring blood, ultrasound, surgical thoracostomy.

Days off are often well-earned.

Did you get any specific training/ what did that entail?

As mentioned earlier, all paramedics in our part of AV are postgraduate qualified a couple of times over. In addition to the year or so at Monash part-time, there is a 6-week vocational training program at Essendon Base, a two-week dedicated winch rescue training course, followed by 4+months with a clinical instructor before you can work as a solo MFP. All instructors are senior MFPs, with extensive on-road and flight experience.

Many of them are dual-qualified current or former critical care nurses. The training period from commencement at Monash through to working solo is about 2 years, and the scrutiny is very high. Each case you lead is placed under intense examination, but in a supporting environment. It is a hard slog, that’s not even acknowledging the selection process, which traditionally has a 20-30% pass rate. It’s a tough job to get, and of the ~4000 or paramedics in Victoria, only 45 are MFPs, and less than 100 people have ever performed the role since its inception in 1986.

What are the most rewarding parts of your area of work?

The autonomy and clinical challenges are the hallmarks of the role. There are few other jobs in health care with such a high exposure to critically unwell patients in a dynamic environment, a diverse skillset, and such a great team of people to work with. Often, these challenges are in a resource poor environment, and complex logistical and clinical decision making is required. It’s a job of identifying a range of problems and trying to solve all of them to the best of your ability. As a ground-based paramedic, you would probably feel like you help people on a more regular basis in the primary health care space, whereas in this role, due to people often being critically unwell or injured, you have less cases where you feel you’ve made a significant difference, but some are very significant. There’s been a number of cases over my career where a life has been saved, and that’s enough for me.

What are the most difficult parts of your area of work?

The whole career of paramedicine is incredibly rewarding but it can be taxing. Long nightshifts, high operational and training workloads and confronting scenes managing sick patients, and/or relatives of critically unwell or injured persons can all add up to a significant burden. Additionally, much of our training is on our rostered days off or during leave blocks. However, we have to meet many clinical and aviation as part of the role. The job is not particularly family friendly, so you have to make a number of concessions, or have a very understanding family. Both are applicable to me.

Flexible work arrangements are challenging to access and taking extra time off is very hard. A ground-based paramedic can take a shift off and it will be covered for them by our rostering department, but we have to backfill all our own shifts, and if no-one can do it, then no time off. MFPs cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to train and keep trained, so staffing numbers are understandably tight.

What do you carry on you during a shift?

Our flight suits have too many pockets, but in addition to all the specialist gear, I have a 20 year old stethoscope that’s still going strong, some checklists for clinical procedures, some pens, a multi-tool, and a notepad. Always my phone with ApplePay so I can grab a coffee at whichever destination hospital we land at. The longer I’ve been in the job, the less I carry.

How do you destress after a shift and selfcare?

After shift, it’s usually straight home to see the kids, my wife and our lovable idiot boxer dog. We have a busy life with a small rural property, so immediate post shift rest is rare. There are clothes to fold, dishes to wash, uni work to do. But I’ll usually get at least half an hour in for a beer with my wife and to hear about her day. I talk about my job a lot to other ambos, our peer support staff, but less and less to my wife other than anything funny or interesting that may have happened. She’s not in healthcare and being a paramedic has unquestionably dominated our working lives (she can still recite the contraindications to suxamethonium), so I try and gain a bit more understanding into her working life rather than carry on about mine.

What different areas of paramedicine have you worked in?

I have worked in rural and remote areas but spent the vast majority of my ground time in inner Melbourne and Sydney. I have worked as a clinical instructor, team manager, and currently I spend a bit of time acting in the role as a Clinical Support Officer in the South Gippsland and Latrobe Valley areas, teaching and supporting junior through to senior staff, whilst still responding to cases (often the best opportunity to teach). I have also taught into the undergraduate and postgraduate paramedicine programs at Monash since 2003.

Can you share some night shift tips?

At this point in my career, it’s purely about surviving. My PhD work is in part looking at physical activity and nutrition in shift workers, and the best tips from the chronobiology pros I work with are:

- Exercise the morning of, then sleep prior. Or, sleep late, then exercise (my preference before kids, now there’s no such thing as a sleep in.)

- Don’t eat anything between 1-4AM.

- Avoid the crap food that everyone brings in. The nurses station often looks like a 7-Eleven has exploded.

- Drink plenty of water.

- The middle of the night is not the time to be completing your clinical reading etc.

- Eat decent brekky at work at the end of the shift, then head home for sleep, at which time it should be settled in your stomach, ready for sleep.

- Turn your phone off for sleep. Not anywhere near your room.

- Plan for some point in your career for night shifts to end. Night shift is a young person’s game!

What’s in your lunch box!

I’m the world’s most boring eater. I have a wife who is one of the world’s greatest cooks, and it’s such a waste on me.

On a day shift, it’s muesli for breakfast, 3 coffees before lunch, mixed salad or leftovers for lunch (usually low GI/low carb lunch as I have massive carb/insulin crashes after lunch), some fruit, and then hopefully home for dinner which is often lamb from our front paddock, with veggies from our back paddock, or some of the other great local produce from our property or the surrounding areas.

Nightshift is a coffee on arrival, pre prepared dinner (we can’t leave the base, so it’s easy to avoid takeaway), cup of tea later on, then nothing until breakfast the next morning, no matter how busy we are. The risk of poor health from eating during the Circadian nadir is well-established.

Can you think of a really funny situation you’ve had while being a paramedic?

Just last week when we winched an injured walker out of the remote wilderness, after the rescue we diverted to another point to pick up the patient’s school teacher to escort the student to the hospital. Once the teacher was onboard, I asked her when they’d last had something to eat or drink, as I was trying to ascertain the patient’s hydration status (it was uncharacteristically hot that day). The teacher just said to me “no, I’m fine thanks”. She obviously thought whilst I was managing her injured student, I was going to prepare the inflight meal for her on the way into hospital. A definite face palm moment.

What is one piece of advice for students you would give who are worried about starting a graduate year?

For nurses and paramedics, it’s the same. You have a bunch of theoretical knowledge, and some experienced clinicians will do some things that don’t align with your textbook learnings. Watch and observe, listen to advice, take note of what people do. Some things you see you will (and should) choose to discard from your practice, some you will take on. Speak up if harm is being done. Careful observation and strategically thought out questions are appreciated. Be respectful, offer to help, keep the patient at the core of your practice. These concepts will serve you well. Healthcare is as a rewarding career as one could hope for. Just make sure you’re equipped and prepared to ride through the ups and downs.

To read about being a flight nurse click here

You must be logged in to post a comment.